Bias in Healthcare

Medical practicioners are committed to equal treatment, but data still show disparities. Learn how to subvert bias to make treatment more equitable.

We highly recommend you first try our interactive demo “When Does Life Spark in a Face?”

Transcript

NARRATOR: How do you know if a face is alive?

For most of us, this isn’t a hard decision.

Take a look at this face.

Is it alive? Can it feel pain?

It should take a fraction of a second to decide: of course not. That’s a Ken doll in his 50s; it’s not a real human. It can’t feel pain. It doesn’t have a mind.

So here’s the more interesting question: where is the tipping point?

Just how “human” does this face need to be for us to start thinking “Okay, there’s a mind in there. This face can feel pain.”

According to psychologists at Dartmouth, the average answer here is about 67%.

Once a face is about 67% human, it looks alive, it looks like it has a mind, and it looks capable of feeling pain.

But this threshold isn’t set in stone. Research shows that if the face in front of you is somehow not like you—let’s say it’s a student from a rival school, someone who has different politics, or even someone from a different racial or ethnic group—these faces (the faces of outgroups) now have to be significantly more human than an in-group face before you’re willing to say they can think or feel.

This isn’t a conscious decision. It’s an implicit bias in perception, ticking away in the background of our minds.

And there’s a natural question that follows: if it’s harder for us to see some faces as “capable of feeling pain,” could this make harming them easier? Even when we’re looking at people who are undeniably 100% human?

It’s possible.

NFL injury reports have shown that Black football players are deemed “okay to play” more often than White players with similar injuries.

And in healthcare, hundreds of analyses show that Black Americans are less likely to receive pain medication than White Americans reporting the same level of pain.

This is true in big cities and small towns, across socioeconomic class, and for many different kinds of pain.

It’s even true for children suffering from appendicitis.

MONICA K. GOYAL, M.D.: Essentially, what we found was when children were presenting with similar levels of pain, Black children had 80% lower odds of receiving opioid medications.

NARRATOR: The simple truth is we see some people’s pain differently. Psychologist Kelly Hoffman and colleagues found that many of us, including medical personnel, implicitly hold the false idea that Black people feel less pain than White people.

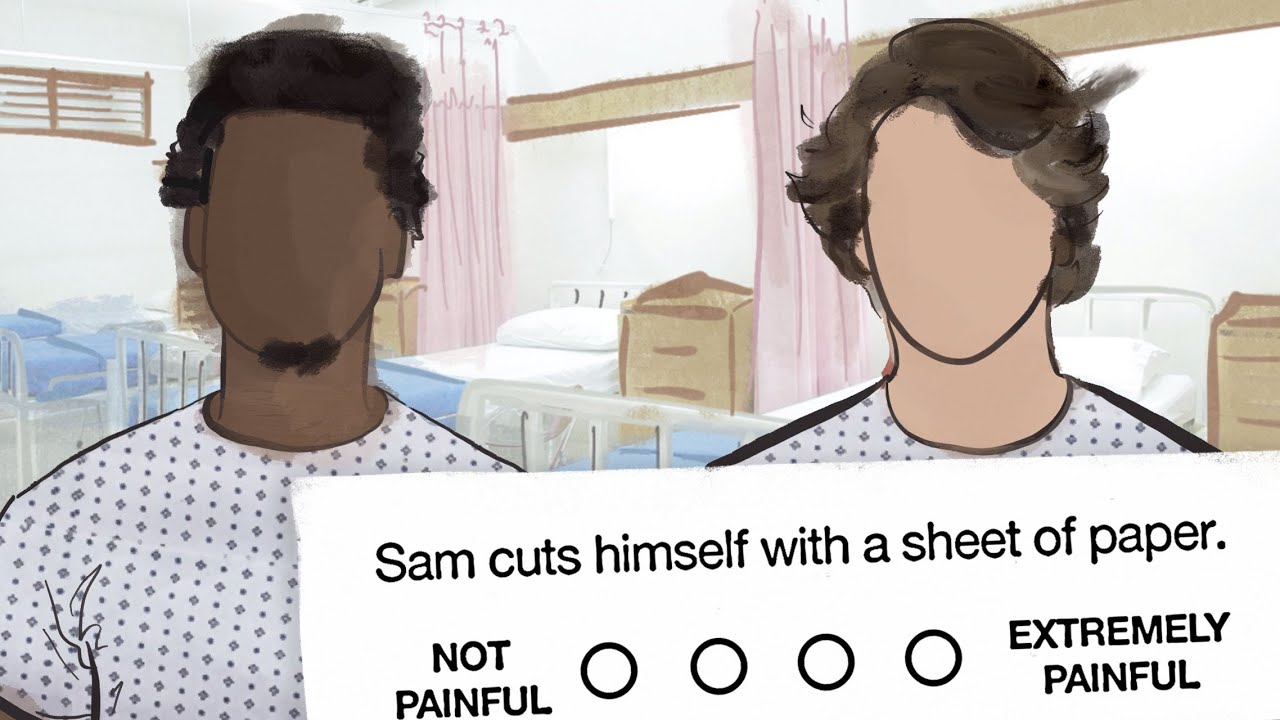

From simple paper cuts to slamming a hand in a car door, the same injury was judged to be “less painful” in her experiments when it happened to this Sam rather than this one.

And this is a bias that affects more than just how we see others’ pain. It can also impact how we treat it.

The medical students and residents who showed the greatest bias when they did this task were not only more likely to endorse false statements like “Black people have thicker skin than White people”; they were also more likely to make inaccurate treatment recommendations for Black patients.

Now remember, these experiments aren’t studying explicit bias. After all, these are doctors — a population of people who have pledged to do no harm. But no matter who we are, hidden biases in our minds can influence what we see—and then how we act.

So let’s talk about solutions.

When it comes to pain management, Professor Mahzarin Banaji has an idea for hospitals – an “in the moment” intervention:

MAHZARIN BANAJI: You type in a painkiller that you want to prescribe to a patient into your electronic system—let’s say Codeine. Your software should return a little graph to you that says “Please note: in our hospital system this is the average amount of painkiller we give to White men, this is the average painkiller we give to Black men for reporting the same level of pain.

You’re the doctor. You’re the expert. Only you can decide what is right for your patient. But it is important to do so with awareness of the pattern of bias in your own healthcare system.

NARRATOR: This carves out a moment for double-checking decisions. Sometimes a well-timed reminder is all we need to outsmart our minds.

Dive deeper

Related modules

Links

Some California hospitals now quantify blood loss after birth by weighing the blood-soaked sponges and pads on a scale. This makes decisions clear for doctors: if a patient is bleeding too much, the scale will say so. Protocols like these have helped California cut its maternal mortality rate by more than half since 2006. Learn more about addressing gender and race disparities in medicine by watching John Oliver’s commentary on Bias in Medicine.

Can artificial intelligence help doctors provide more accurate treatment recommendations? Possibly. Given X-rays of arthritis patients, an algorithm picked up on subtle features that human eyes missed. Even in X-rays deemed “similar” by radiologists, the algorithm found slight differences that helped explain why Black patients were reporting more knee pain than White patients. Read more about the research at BBC News.

“Black and brown patients are systematically undertreated for pain. When treating pain from broken bones to appendicitis, [doctors] give darker-skinned patients, including children, lower doses of analgesics than do white patients, less potent medicine, or nothing at all.” Part of this bias stems from training: many doctors have “heard or been formally taught that Black people don’t feel pain as acutely as white people because they have different biology”. Often – but not always – well-intentioned, race-based medicine influences how U.S. clinicians assess risk, diagnose, treat, and monitor health conditions. But given how race is widely acknowledged as a social construct, should it? Consider the arguments in Stephanie Dutchen’s “Field Correction” at Harvard Medicine.

Pain management is an important part of healthcare, but access to opioids and pain medication is not equal. Across 310 healthcare systems, researchers found a striking discrepancy in the opioid dosage prescribed to patients: Black patients received a mean annual dose that was 36% lower than that given to White patients. We don’t know for sure what’s causing this disparity – are black patients under-medicated, or are white patients over-medicated? Regardless of the ultimate cause, “skin color should not influence the receipt of pain treatment.” Learn more at Patient Engagement HIT.

“Toward more equitable treatment of pain: Addressing bias is not simple, but it is essential, and there are steps that individuals and institutions can take.” Read Dr. Janice Sabin’s recommendations for equalizing medical treatment at The Association of American Medical Colleges.

When women report pain, are their symptoms treated as seriously as men’s? Unfortunately, probably not. When asked to rate the pain of a patient in a video, participants in a study consistently underestimated the amount of pain a woman reported she was experiencing while overestimating the reported pain of a man. This bias in pain perception extends to doctors as well – women are consistently judged to be in less pain than men and to exaggerate their pain. Read more about the research at The Conversation.

References

Goyal, M. K., Kuppermann, N., Cleary, S. D., Teach, S. J., & Chamberlain, J. M. (2015). Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA pediatrics, 169(11), 996-1002.

Hackel, L. M., Looser, C. E., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2014). Group membership alters the threshold for mind perception: The role of social identity, collective identification, and intergroup threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 15-23.

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296-4301.

Krumhuber, E. G., Swiderska, A., Tsankova, E., Kamble, S. V., & Kappas, A. (2015). Real or artificial? Intergroup biases in mind perception in a cross-cultural perspective. PloS one, 10(9), e0137840.

Lee, P., Le Saux, M., Siegel, R., Goyal, M., Chen, C., Ma, Y., & Meltzer, A. C. (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: meta-analysis and systematic review. The American journal of emergency medicine, 37(9), 1770-1777.

Looser, C. E., & Wheatley, T. (2010). The tipping point of animacy: How, when, and where we perceive life in a face. Psychological science, 21(12), 1854-1862.

Meghani, S. H., Byun, E., & Gallagher, R. M. (2012). Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Medicine, 13(2), 150-174.

Trawalter, S., Hoffman, K. M., & Waytz, A. (2012). Racial bias in perceptions of others’ pain. PloS one, 7(11), e48546.

Credits

“Bias in Healthcare” was created and developed by Olivia Kang, Alex Sanchez, Evan Younger, Caitlyn Finton, and Mahzarin Banaji.

Support for Outsmarting Implicit Bias comes from Harvard University and PwC.

Narration by Olivia Kang.

Animation and Editing by Evan Younger.

Images by Olivia Kang and Evan Younger, and adapted via Unsplash.

Music by Terry Devine-King, John Ashton Thomas, and Philip Guyler via Audio Network.

© 2021 President and Fellows of Harvard College